Story Planning for Outworld Ranger & Other Tales

A no-spoilers glimpse at my process as I go about working on the next book in the Outworld Ranger series

Hiya, readers.

This is the second post in my no-spoilers glimpse at my planning process as I go about working on the next Outworld Ranger book. (If you aren’t familiar with the series, you can grab a collection of the first three novels on sale at Amazon for $0.99.)

Today we’re going to dive straight into how the plot comes about through what I call discovery planning.

Brace Yourself: Spreadsheets are on the way. If you deal with spreadsheets at work, I don’t want to trigger your day job PTSD while you’re relaxing on the couch or downing a brandy while a heathen wild-child repeatedly bangs a toy on your noggin.

Before we talk about my current and past processes, I want to make note that I have spent A LOT of time studying story structure, from mythology and religion classes in college all the way through most of the modern classics aimed to help authors and screenwriters create stories (and a few esoteric reads along the way).

In the past, I have primarily written my novels through the discovery writing process. Call it “pantsing” if you want to get on my bad side. Some people call it plot gardening as opposed to plot architecture. Frankly, that comparison makes no sense to me, but I grew up around gardens that provided food for our family for a year, so that may alter how I see things.

Look, everyone plots their stories. Discovery writers just plot as they go. Planners are people who plot ahead of time. And some folks do a mix of the two. I’ve heard of one author who plots ten chapters ahead of where they are but never the whole book at once. There are probably as many ways to write novels as there are authors.

I planned a couple of novels, my first novel and Storm Phase: Lair of the Deadly Twelve, and for the most part I stuck to those plans.

I have followed a hybrid method a few times, notably Chains of a Dark Goddess and Outworld Ranger: Rogue Starship. In both cases, I diverged massively from what I had planned.

In the case of Chains, I only used the planned material for the first third of the novel, at which point it became apparent that something was wrong and it took me weeks to figure things out. Weeks. Rogue Starship was interesting. I diverged and converged then diverged again with what I had planned.

So, I’m a discovery writer, yeah?

Well… maybe?

Yes, I have been a discovery writer, and I do love being surprised when I’m working on a story. Ideas come to me all the time (all the time, non-stop!), and stories and characters frequently surprise me. Usually, the most clever things I do are completely unplanned. (Mitsuki Reel was an unplanned character.)

What I don’t like, however, is getting stuck and writing myself into knots that take forever to unravel. Not fun. And sometimes I create problems that take a lot of effort to solve because in the heat of the moment I come up with some really awesome thing. And yeah, maybe it is awesome. But after a ton of effort, I do not feel awesome about it afterward. Some of the coolest things I’ve ever written were an absolute pain in the ass.

Of course, I do plan stories — while falling asleep, waking up, eating, walking, showering, and driving. I enjoy planning things out ahead of time. And I also enjoy discovering the story at evolves.

I also know that traditional planning methods will not work for me. Story beats and all that. It’s not for me.

So I set about developing a process that would allow me to plan a story while still maintaining some of the benefits of my discovery writing process.

And there’s a reason I did this.

Behind the scenes, I have been planning future novels and book series. When I get stuck on one project, I like to slide over to a different one. It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I finally acknowledged that my brain works that way and gave myself permission to do so. No more banging my head against the wall because I was stuck on one story while another story danced hopelessly through my brain.

No more feeling guilty when working on a shiny new thing while stuck on a work in progress. Because it’s not like my brain just moves on entirely from the stuck project. The gears are still turning, and they’ll get it sorted.

One of the few things I could do over the last year was plan future worlds and books. So I wanted to create a process that would allow me to do that in a detailed and systematic manner that didn’t take the fun and creativity out of the process for me.

I investigated a lot of different ways to record these plans: from a simple text file to Scrivener index cards to Notion (the runner-up) to specialized software like Plottr. And I always came back to one thing: a spreadsheet. Specifically, a spreadsheet customized for the data that tickles my fancies.

So here’s how it goes, assuming all of the world-building has been done and have a basic story concept:

Step 1

Write down a few paragraphs (pen and paper, computer, typewriter, toilet paper and crayon) about the gist of what the story might be about. This is a concept and not a plan. No consideration is given to… Well, anything. Certainly not to how a story should be structured or anything like that. And this step might not even be necessary. I’ve absorbed plot structure from books and movies and tv and comics and books on writing books and movies and tv and comics. So I trust my brain to figure out the structure as I go. (Some writers have different brains, and they need to map those things.)

Something like this would be acceptable: Siv is hired to break into a hard credit bank but runs into trouble when it turns out the entire bank is guarded by mice with laser beams on their heads.

Step 2

Have I written in this world before?

If so, skip to Step 3.

If not, write one to three chapters to get a feel for the tone and the main character’s voice and attitude. As I said in the last post, I do a lot of world development as I write. The most critical world development will likely appear in the first few chapters. To me, though, the tone of the stories is even more important, so I want to get that nailed down with actual prose (that I will likely heavily revise later).

Step 3

Open my spreadsheet and plan out the scenes in a mostly linear fashion. And be irritated about moving information from the first few chapters into the spreadsheet if it’s a new story world.

I will fill out the columns on my spreadsheet as I go and drop back to change things as needed or drag rows to move the scenes around.

Step 4

Happens while Step 3 is in progress. I will fill out the character sections of the spreadsheets as I learn who the characters are and add new ones. It’s possible I will fill out some information on the main characters before this stage, but not a lot of it. And the story will make that stuff change.

Of course, for the Outworld Ranger series, I already know all the main characters, so those sections are just there to remind me of things I might forget: Mitsuki’s skin is teal. Siv’s eyes are orange. Faisal is a grumpy little happy-go-lucky murdering bitch. Yeah, okay, I could never forget that last one.

Step 5

Write the book based on the plan in this spreadsheet.

This is where I’m going to let my creativity shine now. Instead of coming up with wild ideas for scenes as I write them, I’m going to focus my creativity on making those scenes and how they are presented better. The wild ideas, after all, have already been taken care of during the spreadsheet planning phase.

Now, I know this doesn’t seem much like discovery writing and may sound a lot like a structured plan. In fact, it seems a lot like a long synopsis of the sort James Patterson might write, and I suppose it is in some ways.

But the magic, for me, comes in what appears on that spreadsheet in each column.

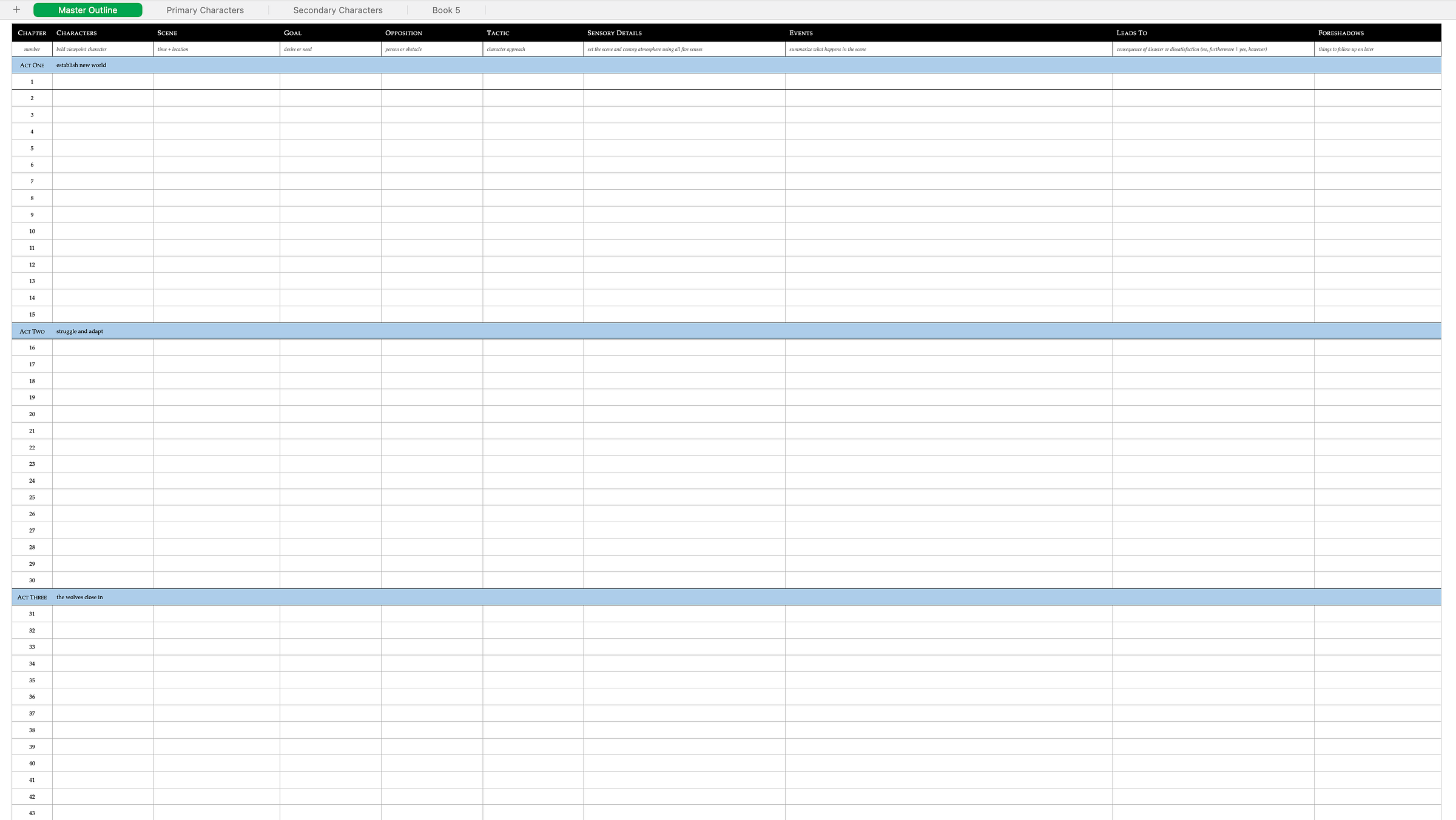

The Spreadsheet

I use Numbers on MacOS, because it’s free, and because I already use Numbers to track my business income and expenses. I’m well-versed in Excel, but I don’t want to pay for it. Numbers is more basic, and I don’t need fancy.

For each series, I use different colors for mood. For example, black and blue for Outworld Ranger and blue and green for Storm Phase.

On the sheet you’ll see some basics like who the characters are and where and when the scene occurs. Nothing unusual there. The key to this all of this is putting myself into the scene and working my way through in a way I would never do with regular story planning of the type I have tried in the past or of any other type I’ve ever seen — and I’ve seen a lot!

The magic starts when I get to the Sensory Details column. At this point, I imagine what it’s like to be in the scene and nail down the sensory details, noting any significant sights, smells, and sounds (touch and taste don’t come up much here, I find).

With the sensory details set, I then write a concise summary of what happens in the scene, playing it out in my head as if I were writing a first draft, only without all the fancy words. I may even include a snippet of dialogue here or there. Whatever helps me get into the character’s head in the story world and make things come to life. And that I will be able to decipher when the time comes for writing out the scenes.

I don’t worry about filling out the columns in order. After setting the first four, I may bounce around and fill out things as they come to me. For example, as I write the synopsis of the events, I may figure out new sensory details that should be noted.

All of this is all done without directly considering structure. Although structure is always in the back of my head as I’m writing, no matter what method I’m using.

You will note that my spreadsheet has five structure delineations. Five acts, four so named and one called Lead-Out. With an expectation of 64 chapters. It could be fewer than 64 chapters or more. I’m not worried about the total number.

Act 1: Establish the New World

Act 2: Struggle and Adapt

Act 3: The Wolves Close In

Act 4: Pay the Price

Act 5: Embrace the New World

I don’t worry much about the act structure. It’s just a rough guide that allows me to judge where I am in the story. I’ll get to each of the transitions with or without them labeled. But if I were to hit a rough patch and not know what to do next, knowing where I am in the story could help me figure out what to do.

Yes, you can probably tell from this that I’m not into the three-act structure. Frankly, I think the notion is kinda dumb. You are told you have three acts and that the second act is twice as long as the others. You are also told the book should have a strong midpoint. And so what does that really give you? Four acts. If you are a planner and you find the middle of the book challenging, start thinking about your stories in terms of four acts. I believe it will help you.

Writers prior to the 1950’s seemed to largely think of stories in terms of four or five acts. And many of the television shows you have watched over the years have followed a five-act structure dictated by commercial breaks.

Other things of interest you might note here are…

Tactic (character approach)

Leads-To (consequence of disaster or dissatisfaction (no, furthermore | yes, however)

Foreshadows (things to follow up on later)

The last one seems pretty self-explanatory.

Leads-To is just way for me to make sure the scene has a point and is going somewhere. Typically, a character tries to achieve a goal and is thwarted from that goal, or they attain the goal only to figure out it’s not really what they wanted or needed.

Tactic… In its essence, this is just a way for me to keep characterization focused in the events of the scene, so I can stay in the character’s head as I summarize the events.

Different characters have different approaches to how they prefer to solve things, not that they don’t use other methods. They absolutely do. But in a crisis, what’s their go-to method for solving a problem.

Silky’s approach is to Scheme with Extreme Delight, and Siv’s approach is to Plan in Detail. Faisal’s approach is to Murder while Vega’s approach is to Fight. Bishop’s is to Repair. Gav’s is to Dig Deep. Oona’s is to Ponder. Tekeru’s is to Research.

These can change over time. Kyralla’s approach is to Anticipate, I think, but in the first book I would say she Doubts. (I didn’t have this system in place at the time, so it’s harder to say.)

So the Tactic column is how the POV character uses their Approach to achieve their goal against the opposition.

So far, I’ve been using this system to plan the next Outworld Ranger novel, a Benevolency Universe short story featuring Mitsuki, and three yet-to-be-revealed series: two epic fantasy sagas and a military sci-fi romp on an alien world.

I didn’t use this system when I started The Crucified Owl, and I regret not having done so. I am likely to soon move the story onto the spreadsheet so I can finish it. The Arthur Paladin Chronicles and a novella I started years ago that has an amazing start then peters out will also get this treatment.

I am using a simplified version of the spreadsheet for tracking what happens in the Storm Phase series since most of the chapters are revisions and expansions and there are only a scattering of new chapters.

Next week, I’m going to give y’all a small example of what a partially filled-in sheet would look like. And maybe after that, I will show you what the Primary Character section of the spreadsheet looks like.

If you have any questions about any of this or want some clarity, drop a comment below.

Be well, everyone!

David Alastair Hayden